This is a cross-post of a post of a post I made to the Benchling Engineering blog. See the original post.

The world of frontend development evolves so quickly that sometimes it feels impossible to keep up. Even worse, what do you do with your existing code when technologies shift? Innovations in languages, libraries, and practices are great, but they’re only useful if they can be used in practice. To enable new technologies, we need good modernization tools to aid in the transition process.

At Benchling, we chose CoffeeScript in 2013, but about a year and a half ago, we recognized that the language was losing steam. The community and the tools were all moving to JavaScript, and with ES2015, JavaScript was getting much, much better. We made a decision: New code will be in JavaScript, and for now, the 200,000 lines of CoffeeScript will stay as-is. We’ll convert code over to JS as we find time for it. We wanted to be entirely on JavaScript, of course, but converting that much code seemed like a gigantic task.

I took that as a challenge, and a year and a half later, I’m happy to say that that gigantic task is now complete. We’re finally at zero lines of CoffeeScript, all with minimal disruption to feature work. At the time, there weren’t good tools for such a big conversion, so I had to help build them. I started contributing to the decaffeinate open source project, became the primary maintainer, and pushed it to completion. This post is about that long journey, and now that a tool like decaffeinate exists, it probably won’t take as long for you. 😄

Why switch to JavaScript?

At Benchling, we build tools to help biologists coordinate experiments, analyze and work with DNA, and more, and one of our strengths is our modern platform. We need to build and iterate quickly, so it’s important that we always have access to the latest and greatest tools. (We’re also hiring!)

We started with CoffeeScript in 2013, and that was the right choice at the time. The JavaScript language was at a standstill, and CoffeeScript overhauled it by introducing arrow functions, classes, destructuring, string templates, array spread, and lots of other cool features. It certainly had problems, like lack of standardization, surprises around variable scoping, and difficulty writing tooling, but it was the best there was.

Over the next few years, JavaScript made a comeback. Inspired largely by many of the CoffeeScript features, the JavaScript committee released the ES2015 spec (a.k.a. ES6) that moved the language up to parity with CoffeeScript in some cases and beyond in other cases, and with Babel, it was possible to use modern JavaScript in any browser without waiting. The community became focused on JavaScript, so the tools got better. ESLint now has hundreds of rules and many competing popular default configurations, Prettier is a whole new class of formatter, and TypeScript and Flow allow advanced type checking while staying true to JS. Switching programming languages is never an easy choice, but it seemed like JavaScript was a safer long-term bet, and it’s easy to use the two side-by-side, so writing new code in JavaScript seemed reasonable.

Having a split codebase is possible, but it ended up hurting productivity when working with older code. Switching back and forth between two languages is a pain, and two frontend languages meant more for new hires to learn and more trivial style rules to keep track of. And, of course, our new tools like ESLint couldn’t help when modifying old CoffeeScript code, where they probably would be most useful. A unified JavaScript codebase seemed like the right end goal.

First idea: convert the code by hand

One day in June 2016, a coworker decided to be ambitious: he was working with a complex 500-line React component, GuideGroupTable.coffee, and he was going to port it to ES6 first to make it easier to work with. Line-by-line, he carefully reworked the syntax and some of the logic until finally, GuideGroupTable.js was ready to try out. It broke the first time, and the second, but after fixing some little mistakes, things seemed to work, and he wrote some additional tests to gain more confidence in the conversion.

Even with tests, and even with a thorough code review, making such a big change to complex code is risky, and it ended up introducing two bugs. In all, converting the code, getting it reviewed, and fixing the resulting bugs took about two engineer-days total. But at least there was a shiny new modern-looking GuideGroupTable.js. One file down, about 1000 more to go.

Math quiz: If every 500 lines of CoffeeScript converted takes 2 days and introduces 2 bugs, how many days and bugs is it for 200,000 lines?

Answer: 800 days (or 6,400 hours), 800 bugs.

Spending over 3 engineer-years on switching programming languages would be a disastrous waste of time, especially for a startup; that’s time that could be spent working on real problems that scientists are facing. At the end of the day, cancer doesn’t care what programming language we use, and if sticking with CoffeeScript is the pragmatic choice, that’s what we’ll do.

Maybe this was just a particularly difficult case and other code would be easier. Even if these estimates are too high by a factor of ten, 640 hours and 80 bugs is still way too much to ask. If we’re going to move off of CoffeeScript at all, there needs to be a better way.

Second idea: the CoffeeScript compiler

In a certain sense, automatically converting CoffeeScript to JavaScript is trivial: just run it through the CoffeeScript compiler. The newest versions of CoffeeScript (which didn’t exist at the time) produce pretty good code, but there’s still quite a bit to be desired:

- It reformats your code: it switches to two-space indentation, it deletes blank lines, it sometimes expands one-liners to multiple lines, and it sometimes joins multi-line expressions into one long line.

- It always uses

varand declares all variables at the top of the file/function. - It sometimes generates awkward code for the sake of strict correctness, like

using

void 0instead ofundefinedor[].indexOf.call(array, x)instead ofarray.indexOf(x). If you’re still on CoffeeScript version 1, you’ll see more issues: that compiler also removes inline comments and doesn’t attempt to use newer JS features like classes and destructuring.

In short, the CoffeeScript compiler is a good compiler, but not a great codebase conversion tool, so we decided to look for other approaches.

Third idea: decaffeinate

We weren’t the only company with this problem, and through some discussions, I heard about a tool called decaffeinate that tried to solve this problem: it took in CoffeeScript and produced modern JavaScript, at least as much as it could. Unlike the CoffeeScript compiler, it keeps your formatting and tries to use modern syntax and patterns.

I installed it and tried it out on our codebase. Out of 1200 files, it failed on about 600 of them. On the plus side, it successfully converted half of the files.

It was promising, but it certainly wasn’t done. Lots of features were explicitly

not supported: ?., for own loops, loops used as expressions, complex class

bodies, and more. And most of the time, you’d get a confusing error like

“Unexpected token” with no further context.

I hadn’t made many GitHub contributions before, but it seemed like a reasonable place to start. I filed some bugs, improved some error reporting, learned the code better and better, and eventually, I was a regular contributor. For the last year or so, I’ve been the primary maintainer.

If you want to try it out, the REPL is a nice interactive environment where you can type or paste some CoffeeScript and see what decaffeinate produces.

How does decaffeinate work?

Is decaffeinate a compiler? Maybe it’s a transpiler? (Is that really any different?) I’d say it’s neither; it’s something else entirely. It’s similar to a compiler, but it has different goals and, in this case, a different architecture.

The CoffeeScript compiler approach: code → AST → code

First, let’s see how the CoffeeScript compiler handles some example code:

1

| |

First, it splits the code up into tokens: IF, IDENTIFIER: isHappy, THEN,

IDENTIFIER: cheer, CALL_START, CALL_END, TERMINATOR.

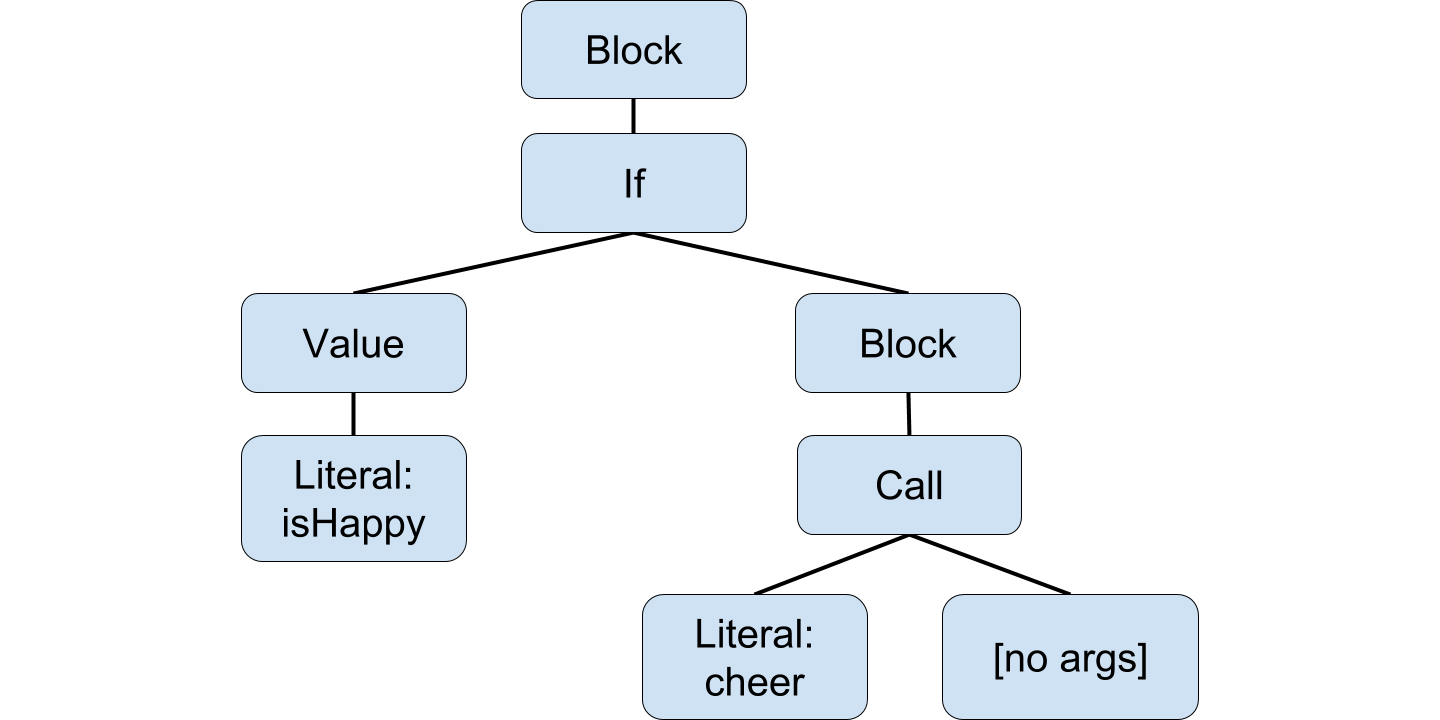

Then, it parses the tokens into an abstract syntax tree (AST):

Each AST node then knows how to format itself into JavaScript code:

1 2 3 | |

Notice that the one-liner was expanded to multiple lines. CoffeeScript doesn’t take any formatting into account when producing output, since it throws away the code and only uses the AST when generating JavaScript.

The decaffeinate approach: targeted replacement

Many of the details in decaffeinate are similar, but it focuses on editing your

code, not rewriting it. Rather than producing new code, it uses the AST and

tokens to generate a list of changes to the code. In this case, decaffeinate

uses the token positions to recognize that the if statement is a one-liner, then

makes these changes:

1 2 3 4 5 6 | |

Those operations are then applied to the original code:

1

| |

Your code only changes where it needs to, and in most cases, the shape of the code is the same as before.

Is this the right architecture? Frankly, it’s unclear, and projects like Prettier have made a compelling argument that codebases should simply have zero manual formatting anyway. But it’s the architecture decaffeinate went with.

Is it even possible?

When building an automatic translation from one programming language to another, you run into an uncomfortable possibility: the problem you’re solving might be impossible.

Let’s take an example. Ideally, CoffeeScript classes can always be converted to JavaScript classes. Here’s one CoffeeScript class that uses a feature you may not have seen:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 | |

Yep, you can do that in CoffeeScript! Not only can you conditionally define methods, you can run arbitrary code at class setup time. JS classes can only consist of plain methods (for now), so there simply isn’t a way to do this. You can try, and you’ll get a syntax error:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 | |

If you’re moving this code over manually, you’d think to yourself “I guess that trick doesn’t work in JavaScript, so I’ll rethink the code”, but that’s not possible with an automated tool.

So how should a tool like decaffeinate approach this? There are a few options:

- Fall back to the CoffeeScript implementation. That’s not so unreasonable, but ideally CS classes would always become JS classes. It’s also not as easy as it sounds, given the different architectures.

- Throw an error, saying that this syntax isn’t supported. Anyone wanting to run decaffeinate on code like this needs to dumb down the code first.

- Find some trick to make it work anyway.

#3 is where decaffeinate really shines: there are lots of little tricks to make the code look as good as possible while still being correct.

Case study: converting array comprehensions

Let’s take a look at some CoffeeScript code:

1

| |

Looks pretty clean (although you’ll get an unpleasant surprise if you forget the parens). JavaScript doesn’t have array comprehensions, so we’ll need to find some alternative.

Here’s how the CoffeeScript compiler handles it:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 | |

Yuck. It works, but it certainly wouldn’t pass code review. Here’s what we really want:

1

| |

Looks pretty clean, and not too different from the original code. But is it

correct? It certainly looks right, but would you be willing to run this

transformation (a for b in c to c.map(b => a)) on hundreds of thousands of lines

of code? As it turns out, it’s not correct. If you want, you can stop reading

and think about what goes wrong.

I implemented this transformation, ran decaffeinate on a few thousand lines of code from work, did lots of testing, including existing automated tests, and it still ended up causing a crash in production.

Here’s the old CoffeeScript:

1

| |

And here’s the new JavaScript:

1

| |

The fundamental problem here is that you might not be working with an array. In

this case, it was a jQuery collection, where map exists, but doesn’t produce an

array.

This problem is all over the place in CoffeeScript: every time you iterate

through something in CoffeeScript, it needs to be array-like. That means you

need arr.length, arr[0], arr[1], etc. When ES2015 came around, they decided to

do things differently: they created the iterable protocol. Any object that wants

to be iterable can expose a Symbol.iterator function that describes how to

iterate through the object. That’s what JavaScript uses for iteration when you

use for (const rhino of rhinos) or children = [...children, baby]. Arrays are

both array-like and iterable, but plenty of JS objects are array-like but not

iterable, and even more objects don’t have map (or have a map that works

differently). Strings, jQuery collections, and FileList (but only in Safari) can

all cause problems here.

Fortunately, there’s a simple built-in function that converts array-like objects

to true arrays: Array.from. To systematically avoid this problem, we can throw

in Array.from anywhere we iterate over anything, and this is what decaffeinate does.

This is one of the toughest design questions of decaffeinate: how important is

correctness really? If a bug only comes up every few thousand lines of code, do

we really want to defensively add Array.from on all iteration operators?

After a lot of thinking, I decided that yes, decaffeinate should be completely correct on all reasonable code. There’s a judgement call about what is “reasonable”, but decaffeinate needs to be trustworthy. decaffeinate’s goal is to speed up the conversion from CoffeeScript to JS, and if you need to extensively manually test your code after decaffeinate, it will take much, much longer. decaffeinate needs to be as stable as any compiler.

If you use decaffeinate, you’ll probably see Array.from all over the place. You

can disable it with the --loose option, but I’d recommend instead looking through

the resulting code and only removing Array.from when you’re confident that the

object you’re working with is already an array.

Reaching super-stability

Between July and December 2016, decaffeinate slowly got more and more stable when run on the Benchling code. 500 files failing, then 350, then 200, then 50, then 10, then 5, then 0. After some cheers and excitement, I ran the tests for the newly-decaffeinated codebase, and they crashed immediately. More work to do, I guess. I fixed a bug, I fixed another bug, I tracked down and fixed an ESLint bug, I upgraded Babel to work around a Babel bug, I kept on iterating, and finally it got to a point of the tests passing.

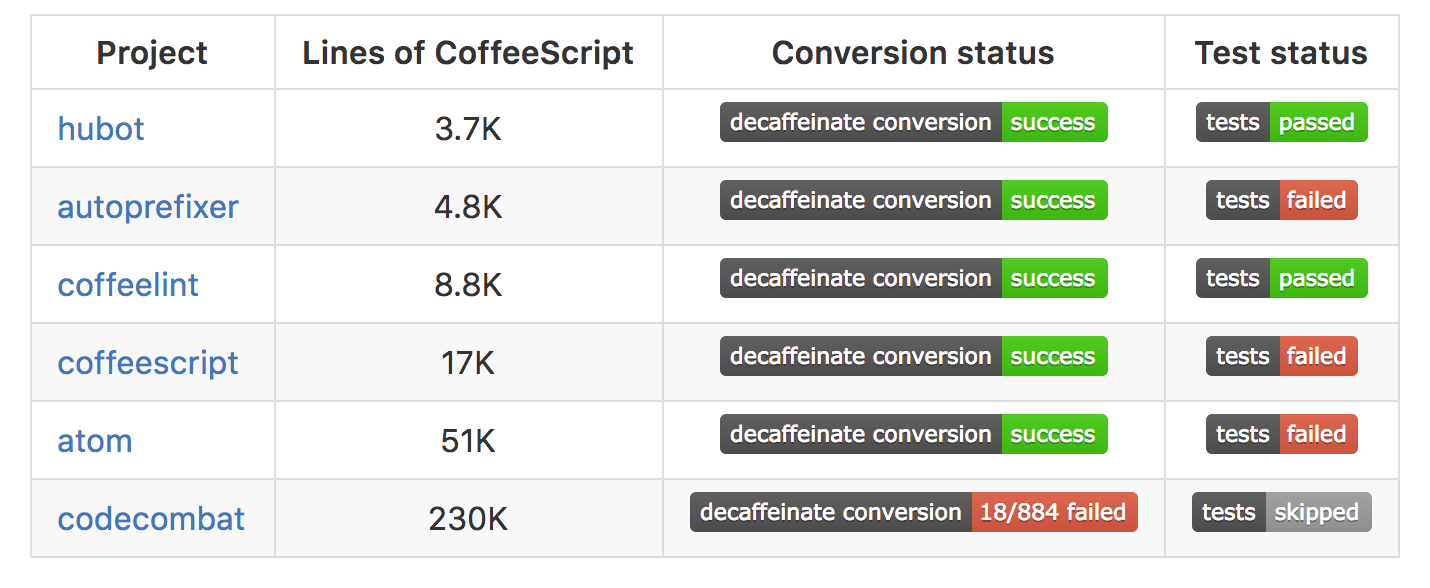

So now what? decaffeinate seemed to work great on the code that was covered by tests, but what about the code that wasn’t covered by tests? I could write 100,000 lines of tests to try to get full code coverage, but that might take a while. I needed to find more test cases for decaffeinate, and fortunately, the internet has no shortage of CoffeeScript code. I set up a build system that would run decaffeinate on a bunch of projects, patch them to use Babel, then run all of the tests. A status board on the README was also a good motivating factor and a good way to see progress. Here were some of the results early on:

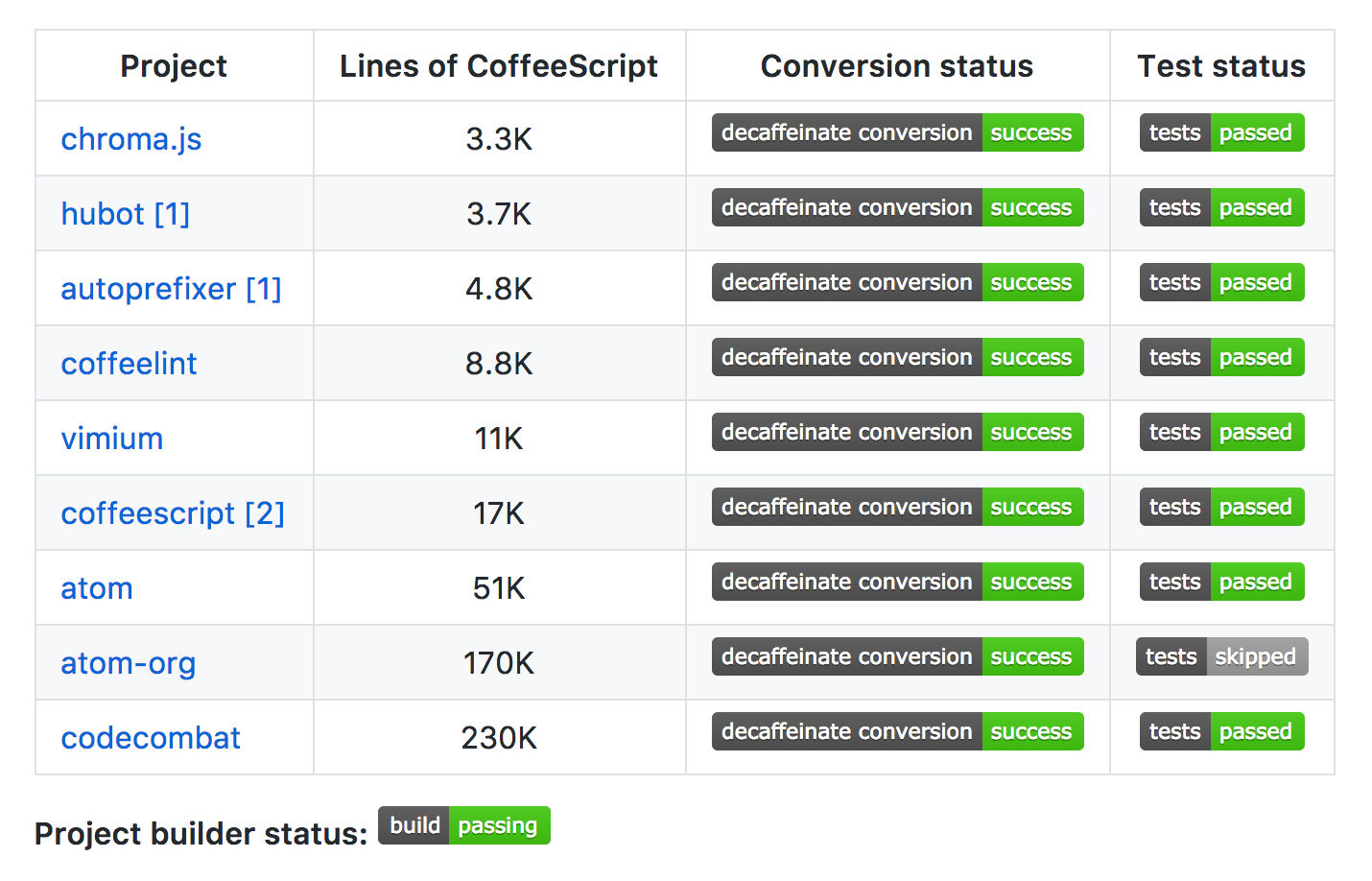

Testing out decaffeinate on codebases with a wide variety of authors and coding styles worked out great, and setting up the tests allowed me to discover the most critical bugs. There were lots and lots of bugs, but after a few months, I finally got everything working:

It’s rare that you ever get to say that a software project is complete, but I think this is one of those times. Technically, there’s still a bit more that would be useful, and I did some follow-up work to add a suggestions system and clean up usage, but decaffeinate is now in maintenance mode.

Getting to zero

With decaffeinate stable, we were finally at a point where it wasn’t crazy to run it on large swaths of code without extensive testing or review. So what do you do when you have a tool like that and 150,000 lines of CoffeeScript to convert? Somehow, converting it all at once seemed a little worrying.

Here’s the strategy we took: every Tuesday, we’d pick off a large chunk of code

and run it through decaffeinate, first about 5000 lines, then larger and larger

chunks, up to 20,000 lines at once. We always had a 100%-machine-automated set

of commits, then two of us scanned through the converted code and made any safe

cleanups we could find. That did not mean blindly removing all usages of

Array.from or other decaffeinate artifacts; it meant fixing formatting, removing

unused variables, renaming autogenerated variables to other names, etc. The code

at the end wasn’t pristine, but it was JavaScript, and it was much better than

what the CoffeeScript compiler gives.

The stability work paid off, and after repeating this process for about 10 weeks, we finally were able to get it completely to zero with very few issues. That also meant that it was possible to remove CoffeeScript from the build system, disable CoffeeLint, and delete our CoffeeScript style guide.

In a sense, the job still isn’t done. We still have lots of files with decaffeinate artifacts and disabled lint rules that should eventually be manually cleaned up. One of our biggest auto-converted files starts with this:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 | |

So it’s not perfect, but it’s pretty easy to do the remaining cleanup work as you go.

Let’s compare my original estimate with the actual cost of converting 200,000 lines of code:

Estimated cost without decaffeinate: 6,400 hours, 800 bugs.

Actual cost with decaffeinate: ~100 hours, ~5 bugs.

(Not including the work on decaffeinate, which was in my spare time. 😄).

Those 100 hours were mostly spent spot-checking and cleaning up the resulting JS, code reviewing those cleanups, manually testing the relevant features, and deploying the changes gradually to reduce risk. 2000 lines of code per hour seemed like a safe rate, but theoretically, it could have all been done at once, and if you’re in a hurry, you could probably go much faster.

What went wrong?

decaffeinate is extremely stable, but the conversion process still wasn’t without its bugs. By far, the largest source of bugs was human error. Let’s look at some code, before and after decaffeinate:

1 2 3 | |

1 2 3 4 | |

decaffeinate moved the default param to an if statement in order to be

technically correct, wrapped itemIdsToKeep in Array.from, and changed the in

operator to the includes method. The if statement and the Array.from could both

use cleanup, and in this case we played it safe and only removed the Array.from,

since it clearly seemed like an array:

1 2 3 4 | |

As it turns out, itemIdsToKeep was not always an array. Purely by mistake, it

could sometimes be a DOM event instead. Both CoffeeScript and Array.from

silently treat it as the empty array in that case, but removing Array.from

exposed the crash.

This is an example of a theme that occurred a number of times: decaffeinate tends to break on code that is already buggy.

Let’s look at another example. Here’s some CoffeeScript before and JavaScript after:

1 2 3 | |

1 2 3 4 | |

Seems pretty simple, right? What could go wrong?

As it turns out, the problem wasn’t so much a conversion error as an unexpected

consequence in switching compilers: switching from CoffeeScript to Babel enables

strict mode. Without strict mode, assigning to a non-writable property is a

no-op, and in strict mode it crashes. In this case, response was supposed to be

an object, but instead was sometimes the empty string, which meant that the

assignment simply did nothing. This was just a bug, but it was a benign bug

before and switching to Babel made it a crashing bug.

How can you avoid running into these same problems? Some ideas:

- Try to defer extensive manual cleanups until you’re working heavily with the code and are comfortable testing all of its edge cases. Over and over, we found that a cleanup that seemed safe actually had subtle flaws, and often times it was best to just go with the decaffeinate output.

- You may want to move to strict mode separately from moving to JS. One way to do this is with the babel-plugin-transform-remove-strict-mode Babel plugin. That will keep you on the lookout for the types of errors that arise in strict mode.

Other things to know before using decaffeinate

Here are some more things to keep in mind:

The hardest problem that decaffeinate had to solve is handling

thisbeforesuperin constructors, which is allowed in CS but not in JS. There’s a hack to trick Babel and TypeScript into allowing it, but it’s an ugly hack that you should remove ASAP after running decaffeinate.To help run decaffeinate along with other tools, I wrote a tool called bulk-decaffeinate that runs decaffeinate, several jscodeshift transforms (e.g. converting code to JSX),

eslint --fixand several other steps. You’ll probably want to either use that tool or one you write yourself, since decaffeinate is more of a building block.There have been some great previous blog posts on decaffeinate: Converting a large React Codebase from Coffeescript to ES6 and Decaffeinating a Large CoffeeScript Codebase Without Losing Sleep.

The decaffeinate docs have some pages to help you through the process: the Conversion Guide has some practical advice on running decaffeinate on a big codebase, and the Cleanup Suggestions page lists most of the subtleties you’ll see in the converted code. You can also drop in on Gitter to ask questions!

Every project and team is different, though, so regardless of how you approach it, you’ll likely need some real effort and care. But hopefully, once the conversion strategy, the configuration, and any other details are figured out, the gruntwork will all be safely handled by decaffeinate!

Migration tools let you focus on what’s important

Programming is full of tradeoffs, and a common pitfall is to focus too much on your code when you should be focusing on the real problem that you’re solving. Whether it’s formatting, variable names, code structure, or even what programming language to use, none of it matters if the product doesn’t actually help people. Big code migrations can sometimes feel necessary and benefit in the long run, but they can also be a big distraction and a massive time sink. It’s often an awkward tradeoff, but with solid migration tools like decaffeinate, you can get the best of both worlds: you can benefit from the latest tools and practices while still focusing your time and brainpower on solving real problems and helping people.